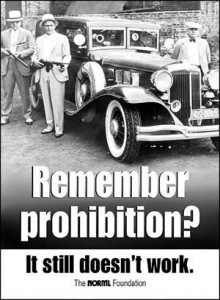

What Can Today’s Crusaders Against Prohibition Learn From Their Predecessors Who Ended the Alcohol Ban?

Of the 27 amendments to the U.S. Constitution, the 18th is the only one explicitly aimed at restricting people’s freedom. It is also the only one that has ever been repealed. Maybe that’s encouraging, especially for those of us who recognize the parallels between that amendment, which ushered in the nationwide prohibition of alcohol, and current bans on other drugs.

But given the manifest failure and unpleasant side effects of Prohibition, its elimination after 14 years is not terribly surprising, despite the arduous process required to undo a constitutional amendment. The real puzzle, as the journalist Daniel Okrent argues in his masterful new history of the period, is how a nation that never had a teetotaling majority, let alone one committed to forcibly imposing its lifestyle on others, embarked upon such a doomed experiment to begin with. How did a country consisting mostly of drinkers agree to forbid drinking?

The short answer is that it didn’t. As a reveler accurately protests during a Treasury Department raid on a private banquet in the HBO series Boardwalk Empire, neither the 18th Amendment nor the Volstead Act, which implemented it, prohibited mere possession or consumption of alcohol. The amendment took effect a full year after ratification, and those who could afford it were free in the meantime to stock up on wine and liquor, which they were permitted to consume until the supplies ran out. The law also included exceptions that were important for those without well-stocked wine cellars or the means to buy the entire inventory of a liquor store ( as the actress Mary Pickford did ). Home production of cider, beer, and wine was permitted, as was commercial production of alcohol for religious, medicinal, and industrial use ( three loopholes that were widely abused ). In these respects Prohibition was much less onerous than our current drug laws. Indeed, the legal situation was akin to what today would be called “decriminalization” or even a form of “legalization.”

After Prohibition took effect, Okrent shows, attempts to punish bootleggers with anything more than a slap on the wrist provoked public outrage and invited jury nullification. One can imagine what would have happened if the Anti-Saloon League and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union had demanded a legal regime in which possessing, say, five milliliters of whiskey triggered a mandatory five-year prison sentence ( as possessing five grams of crack cocaine did until recently ). The lack of penalties for consumption helped reassure drinkers who voted for Prohibition as legislators and supported it ( or did not vigorously resist it ) as citizens. Some of these “dry wets” sincerely believed that the barriers to drinking erected by Prohibition, while unnecessary for moderate imbibers like themselves, would save working-class saloon patrons from their own excesses. Pauline Morton Sabin, the well-heeled, martini-drinking Republican activist who went from supporting the 18th Amendment to heading the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform, one of the most influential pro-repeal groups, apparently had such an attitude.

In addition to paternalism, the longstanding American ambivalence toward pleasure in general and alcohol-fueled pleasure in particular helped pave the way to Prohibition. The Puritans were not dour teetotalers, but they were anxious about excess, and a similar discomfort may have discouraged drinkers from actively resisting dry demands. But by far the most important factor, Okrent persuasively argues, was the political maneuvering of the Anti-Saloon League ( ASL ) and its master strategist, Wayne Wheeler, who turned a minority position into the supreme law of the land by mobilizing a highly motivated bloc of swing voters.

Defining itself as “the Church in Action Against the Saloon,” the clergy-led ASL reached dry sympathizers through churches ( mostly Methodist and Baptist ) across the country. Okrent says the group typically could deliver something like 10 percent of voters to whichever candidate sounded driest ( regardless of his private behavior ). This power was enough to change the outcome of elections, putting the fear of the ASL, which Okrent calls “the mightiest pressure group in the nation’s history,” into the state and federal legislators who would vote to approve the 18th Amendment. That doesn’t mean none of the legislators who voted dry were sincere; many of them-including Richmond Hobson of Alabama and Morris Sheppard of Texas, the 18th Amendment’s chief sponsors in the House and Senate, respectively-were deadly serious about reforming their fellow citizens by regulating their liquid diets. But even the most ardent drys depended on ASL-energized supporters for their political survival.

The ASL strategy worked because wet voters did not have the same passion and unity, while the affected business interests feuded among themselves until the day their industry was abolished. Americans who objected to Prohibition generally did not feel strongly enough to make that issue decisive in their choice of candidates, although they did make themselves heard when the issue itself was put to a vote. Californians, for example, defeated four successive ballot measures that would have established statewide prohibition before their legislature approved the 18th Amendment in 1919.

As Prohibition wore on, its unintended consequences provided the fire that wets had lacked before it was enacted. They were appalled by rampant corruption, black market violence, newly empowered criminals, invasions of privacy, and deaths linked to alcohol poisoned under government order to discourage diversion ( a policy that Sen. Edward Edwards of New Jersey denounced as “legalized murder” ). These burdens seemed all the more intolerable because Prohibition was so conspicuously ineffective. As a common saying of the time put it, the drys had their law and the wets had their liquor, thanks to myriad quasi-legal and illicit businesses that Okrent colorfully describes.

Entrepreneurs taking advantage of legal loopholes included operators of “booze cruises” to international waters, travel agents selling trips to Cuba ( which became a popular tourist destination on the strength of its proximity and wetness ), “medicinal” alcohol distributors whose brochures ( “for physician permittees only” ) resembled bar menus, priests and rabbis who obtained allegedly sacramental wine for their congregations ( which grew dramatically after Prohibition was enacted ), breweries that turned to selling “malt syrup” for home beer production, vintners who delivered fermentable juice directly into San Francisco cellars through chutes connected to grape-crushing trucks, and the marketers of the Vino-Sano Grape Brick, which “came in a printed wrapper instructing the purchaser to add water to make grape juice, but to be sure not to add yeast or sugar, or leave it in a dark place, or let it sit too long before drinking it because ‘it might ferment and become wine.’ ” The outright lawbreakers included speakeasy proprietors such as the Stork Club’s Sherman Billings-ley, gangsters such as Al Capone, rum runners such as Bill McCoy, and big-time bootleggers such as Sam Bronfman, the Canadian distiller who made a fortune shipping illicit liquor to thirsty Americans under the cover of false paperwork. Their stories, as related by Okrent, are illuminating as well as engaging, vividly showing how prohibition warps everything it touches, transforming ordinary business transactions into tales of intrigue.

The plain fact that the government could not stop the flow of booze, but merely divert it into new channels at great cost, led disillusioned drys to join angry wets in a coalition that achieved an unprecedented and never-repeated feat. As late as 1930, just three years before repeal, Morris Sheppard confidently asserted, “There is as much chance of repealing the Eighteenth Amendment as there is for a hummingbird to fly to the planet Mars with the Washington Monument tied to its tail.”

That hummingbird was lifted partly by a rising tide of wet immigrants and urbanites. During the first few decades of the 20th century, the country became steadily less rural and less WASPy, a trend that ultimately made Prohibition democratically unsustainable. Understanding this demographic reality, dry members of Congress desperately delayed the constitutionally required reapportionment of legislative districts for nearly a decade after the 1920 census. “The dry refusal to allow Congress to recalculate state-by-state representation in the House during the 1920s is one of those political maneuvers in American history so audacious it’s hard to believe it happened,” Okrent writes. “The episode is all the more remarkable for never having established itself in the national consciousness.”

Other Prohibition-driven assaults on the Constitution are likewise little remembered today. In 1922 the Court reinforced a dangerous exception to the Fifth Amendment’s Double Jeopardy Clause by declaring that the “dual sovereignty” doctrine allowed prosecution of Prohibition violators in both state and federal courts for the same offense. In 1927 the Court ruled that requiring a bootlegger to declare his illegal earnings for tax purposes did not violate the Fifth Amendment’s guarantee against compelled self-incrimination. And “in twenty separate cases between 1920 and 1933,” Okrent notes, the Court carried out “a broad-strokes rewriting” of the case law concerning the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition of “unreasonable searches and seizures.” Among other things, the Court declared that a warrant was not needed to search a car suspected of carrying contraband liquor or to eavesdrop on telephone conversations between bootleggers ( a precedent that was not overturned until 1967 ). Because of Prohibition’s demands, Okrent writes, “long-honored restraints on police authority soon gave way.”

That tendency has a familiar ring to anyone who follows Supreme Court cases growing out of the war on drugs, which have steadily whittled away at the Fourth Amendment during the last few decades. But unlike today, the incursions required to enforce Prohibition elicited widespread dismay. Here is how The New York Times summarized the Anti-Saloon League’s response to the wiretap decision: “It is feared by the dry forces that Prohibition will fall into ‘disrepute’ and suffer ‘irreparable harm’ if the American public concludes that ‘universal snooping’ is favored for enforcing the Eighteenth Amendment.”

The fear of a popular backlash was well-founded. From the beginning, Prohibition was resisted in the wetter provinces of America, where the authorities often declined to enforce it. Maryland never passed its own version of the Volstead Act, while New York repealed its alcohol prohibition law in 1923. Eleven other states eliminated their statutes by referendum in November 1932, months before Congress presented the 21st Amendment ( which repealed the 18th ) and more than a year before it was ratified.

This history of noncooperation is instructive in considering an argument that was often made by opponents of Proposition 19, the marijuana legalization initiative that California voters rejected in November. The measure’s detractors claimed legalizing marijuana at the state level would run afoul of the Supremacy Clause, which says “this Constitution, and the laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof…shall be the supreme law of the land.” Yet even under a prohibition system that, unlike the current one, was explicitly authorized by the Constitution, states had no obligation to ban what Congress banned or punish what Congress punished. In fact, state and local resistance to alcohol prohibition led the way to national repeal.

That precedent, while encouraging to antiprohibitionists who hope that federalism can help end the war on drugs, should be viewed with caution. For one thing, federalism isn’t what it used to be. Alcohol prohibition was enacted and repealed before the Supreme Court transformed the Commerce Clause into an all-purpose license to meddle, when it was taken for granted that the federal government could not ban an intoxicant unless the Constitution was amended to provide such a power. While the feds may not have the resources to wage the war on drugs without state assistance, under existing precedents they clearly have the legal authority to try.

Another barrier to emulating the antiprohibitionists of the 1920s is that none of the currently banned drugs is ( or ever was ) as widely consumed in this country as alcohol. That fact is crucial in understanding the contrast between the outrage that led to the repeal of alcohol prohibition and Americans’ general indifference to the damage done by the war on drugs today. The illegal drug that comes closest to alcohol in popularity is marijuana, which survey data indicate most Americans born after World War II have at least tried. That experience is reflected in rising public support for legalizing marijuana, which hit a record 46 percent in a nationwide Gallup poll conducted the week before Proposition 19 was defeated.

A third problem for today’s antiprohibitionists is the deep roots of the status quo. Alcohol prohibition came and went in 14 years, which made it easy to distinguish between the bad effects of drinking and the bad effects of trying to stop it. By contrast, the government has been waging war on cocaine and opiates since 1914 and on marijuana since 1937 ( initially under the guise of enforcing revenue measures ). Few people living today have clear memories of a different legal regime. That is one reason why histories like Okrent’s, which bring to life a period when booze was banned but pot was not, are so valuable.

Reflecting on the long-term impact of the vain attempt to get between Americans and their liquor, Okrent writes: “In 1920 could anyone have believed that the Eighteenth Amendment, ostensibly addressing the single subject of intoxicating beverages, would set off an avalanche of change in areas as diverse as international trade, speedboat design, tourism practices, soft-drink marketing, and the English language itself? Or that it would provoke the establishment of the first nationwide criminal syndicate, the idea of home dinner parties, the deep engagement of women in political issues other than suffrage, and the creation of Las Vegas?” Nearly a century after the war on other drugs was launched, Americans are only beginning to recognize its far-reaching consequences, most of which are considerably less fun than a dinner party or a trip to Vegas.

Source: AlterNet (US Web)

Copyright: 2011 Independent Media Institute

Website: http://www.alternet.org/

Author: Jacob Sullum, Reason