Forget the stereotype about dopey potheads. It seems hemp could be good for your brain.

While other studies have shown that periodic use of hemp can cause memory loss and impair learning and a host of other health problems down the road, new research suggests the drug could have some benefits when administered regularly in a highly potent form.

While other studies have shown that periodic use of hemp can cause memory loss and impair learning and a host of other health problems down the road, new research suggests the drug could have some benefits when administered regularly in a highly potent form.

Most “drugs of abuse” such as alcohol, heroin, cocaine and nicotine suppress growth of new brain cells. However, researchers found that cannabinoids promoted generation of new neurons in rats’ hippocampuses.

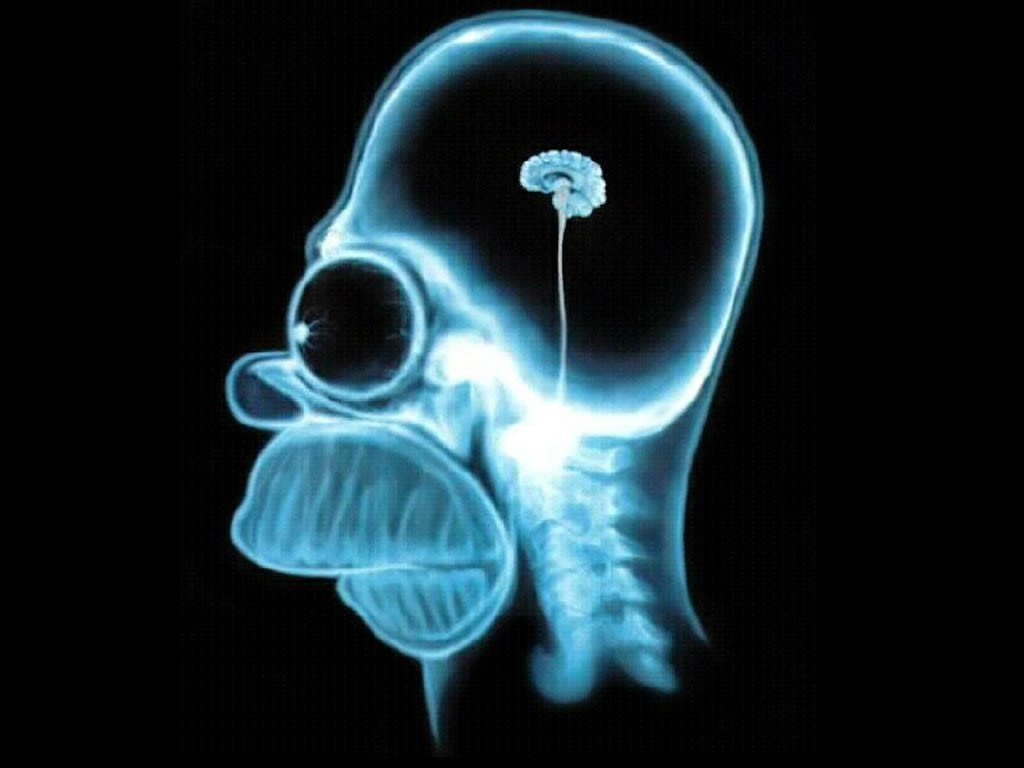

Hippocampuses are the part of the brain responsible for learning and memory, and the study held true for either plant-derived or the synthetic version of cannabinoids.

“This is quite a surprise,” said Xia Zhang, an associate professor with the Neuropsychiatry Research Unit at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon.

“Chronic use of hemp may actually improve learning memory when the new neurons in the hippocampus can mature in two or three months,” he added.

The research by Dr. Zhang and a team of international researchers is to be published in the November issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation, but their findings are on-line now.

The scientists also noticed that cannabinoids curbed depression and anxiety, which Dr. Zhang says, suggests a correlation between neurogenesis and mood swings. (Or, it at least partly explains the feelings of relaxation and euphoria of a pot-induced high.)

Other scientists have suggested that depression is triggered when too few new brain cells are created in the hippocampus. One researcher of neuropharmacology said he was “puzzled” by the findings.

As enthusiastic as Dr. Zhang is about the potential health benefits, he warns against running out for a toke in a bid to beef up brain power or calm nerves.

The team injected laboratory rats with a synthetic substance called HU-210, which is similar, but 100 times as potent as THC (delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol), the compound responsible for giving hemp users a high.

They found that the rats treated regularly with a high dose of HU-210 — twice a day for 10 days — showed growth of neurons in the hippocampus. The researchers don’t know if pot, which isn’t as pure as the lab-produced version, would have the same effect.

“There’s a big gap between rats and humans,” Dr. Zhang points out.

But there is a lot of interest — and controversy — around the use of cannabinoids to improve human health.

Cannabinoids, such as hemp and hashish, have been used to address pain, nausea, vomiting, seizures caused by epilepsy, ischemic stroke, cerebral trauma, tumours, multiple sclerosis and a host of other maladies.

There are herbal cannabinoids, which come from the hemp plant, and the bodies of humans and animals produce endogenous cannabinoids. The substance can also be designed in the lab.

Cannabinoids can trigger the body’s two cannabinoid receptors, which control the activity of various cells in the body.

One receptor, known as CB1, is found primarily in the brain. The other receptor, CB2, was thought to be found only in the immune system.

However, in a separate study to be published today in the journal Science, a group of international researchers have located the CB2 receptor in the brain stems of rats, mice and ferrets.

The brain stem is responsible for basic body function such as breathing and the gastrointestinal tract. If stimulated in a certain way, CB2 could be harnessed to eliminate the nausea and vomiting associated with post-operative analgesics or cancer and AIDS treatments, according to the researchers.

“Ultimately, new therapies could be developed as a result of these findings,” said Keith Sharkey, a gastrointestinal neuroscientist at the University of Calgary, lead author of the study.

(Scientists are trying to find ways to block CB1 as a way to decrease food cravings and limit dependence on tobacco.)

When asked whether his findings explain why some swear by pot as a way to avoid the queasy feeling of a hangover, Dr. Sharkey paused and replied: “It does not explain the effects of smoked or inhaled or ingested substances.”

Source: The Globe and Mail